Don’t Give Advice, Be Useful

Always focus on the next most useful thing

“It is not enough for a professional to be right: An advisor’s job is to be helpful.” David Maister - The Trusted Advisor

“I can DO IT!” my 7 year old screams at me. She asked for help with her homework, but now - half way through explaining the place value of numbers - she had enough of my help and was physically and emotionally pushing me away - “I can DO IT already”.

Of course, she proceeded to not be able to do it.

“Yes I know that!” I shouted in exasperation. I was making pancakes for the kids and had only skim-read the recipe. As a result I had forgotten to melt the butter before adding it to the mixture and it was all lumpy. My partner Erin looked over and said “you should have melted the butter before you put it in, would you like me to give you a recipe?”. I had a recipe, but obviously I hadn’t followed it and knew that I had made a mistake. “I KNOW I should have melted the butter, that’s not helpful to me right now!”.

Giving advice is emotionally fraught and complicated. It’s true for 7 year olds, it’s true for me and it’s true for my clients.

Giving advice is an intensely personal thing. The feeling of learning something new sits right next to the feeling of shame for not knowing it in the first place. And worse, in the client/consultant relationship, the client is at least partially complicit in the situation when they come to you.

So, some of the things that might seem “obvious” to you as a consultant can actually be incredibly delicate and problematic. Consider:

- Quickly pointing out potential problems with the situation

- Immediately offering a solution to these problems

- Stating that things are easily solved

You do these things because you want to be seen as an expert, you want to reassure the client that you have the answer and that the client is in good hands.

But think carefully about how these things make the client feel. They can make the client feel stupid, it can place a fair share of blame on the client for the situation and it can make them feel like you didn’t listen carefully enough to their description of the problem before leaping to solutions.

So in this chapter we’re going to look at ways to resist the urge to add immediate value. Instead we have to hold space for a more vulnerable, honest and open relationship with our client - to allow them to open up more fully and to work on things that are useful, even if not in scope.

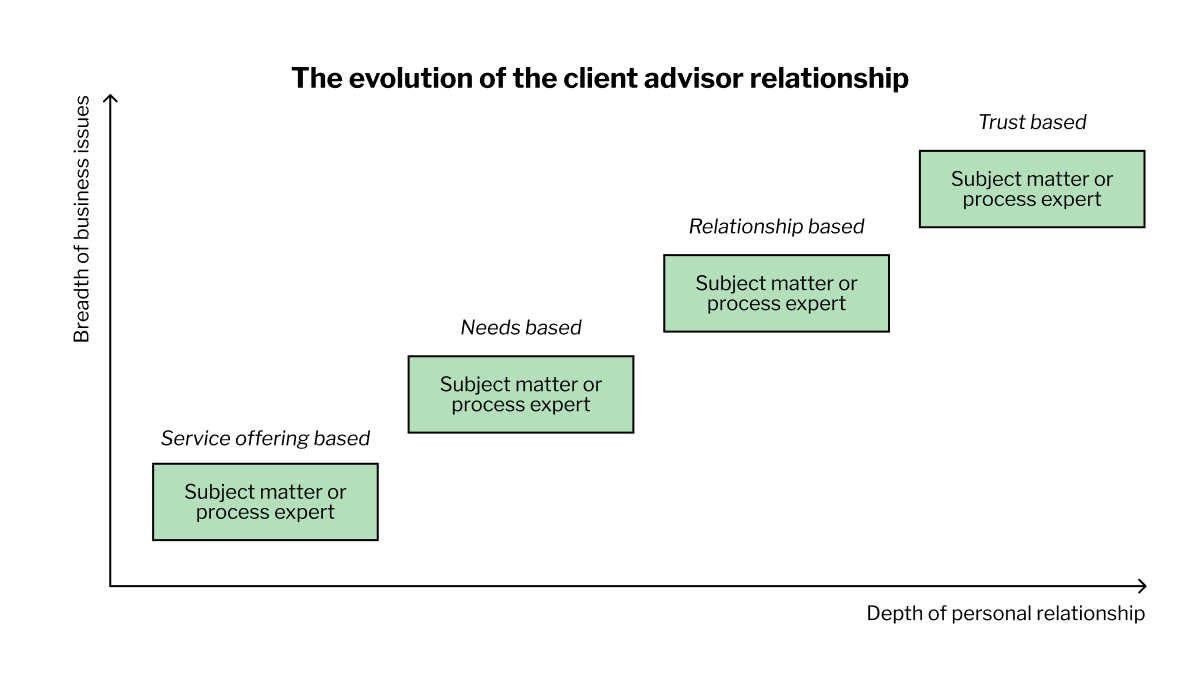

From Consultant to Advisor

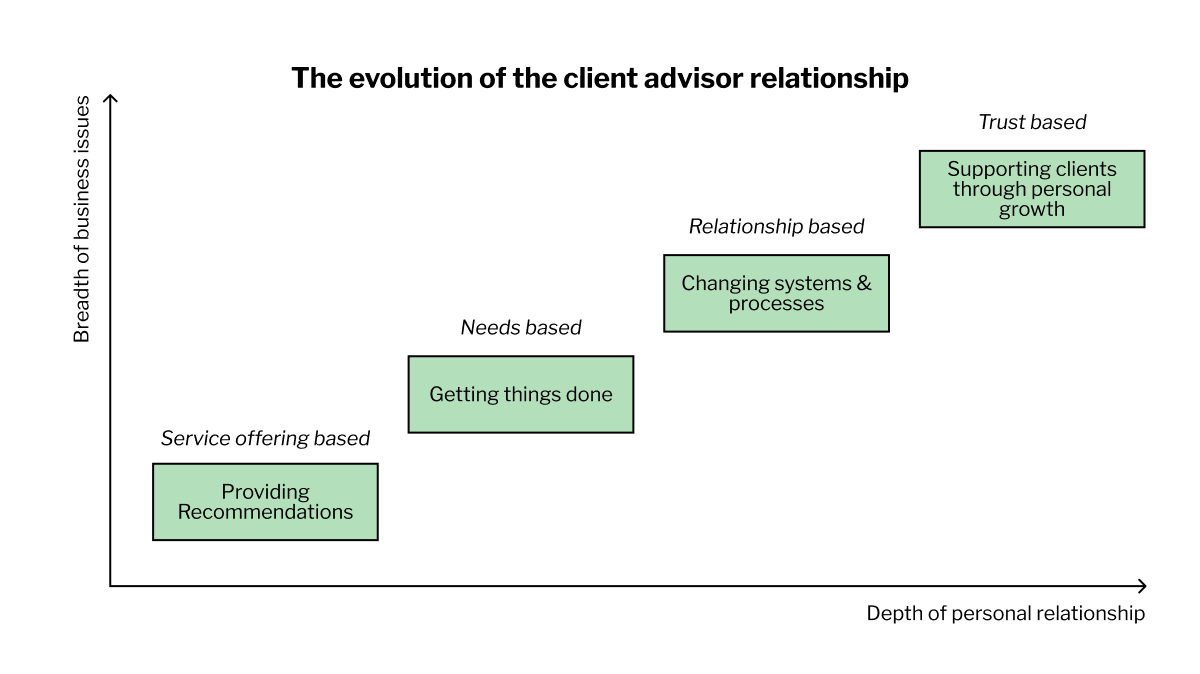

In the book Trusted Advisor by David Maister (highly recommended!) there is a a nice illustration that shows the evolution of client/consultant relationships as you get more senior and more strategic:

Giving advice is fraught even if the problem is well defined and you do know the answer. So when you’re working on strategic, ill-defined projects where there isn’t a right answer - giving advice is incredibly delicate, and in some cases not even possible.

Eventually in your career you might even stop thinking of yourself as a consultant and start thinking of yourself as an advisor.

And as we see in the diagram - in order to get access to the deeper emotional layers of advice giving and receiving we need to formulate a close relationship with our clients.

While giving advice can help you be seen as knowledgeable, it doesn’t necessarily build trust.

“You should…” is a dangerous phrase

One of the biggest mistakes a consultant can make is to think that you’re there to give advice and solve client problems. It’s so easy to let this little phrase creep into your work:

“You should…”

It’s a simple sounding phrase but it gets you in trouble more often than not. It’s problematic for two reasons: it assumes a control of client resources and it’s too prescriptive in form:

1. “You should…” assumes you can allocate client resources

It’s a fundamental mistake to assume that as a consultant we can allocate client resources. We typically don’t have a complete view of everything that the company is working on, we don’t have a detailed understanding of how long things actually take or the full range of dependencies required for them.

Barging into a client saying that they should do something implies a kind of confidence and bravado that can be arrogant at best and ignorant at worst.

Think about the last time you saw a project through from start to finish - the range of complexities, dependencies, hurdles, different work streams and so on required to get it over the finish line are almost certainly missing from the overly-confident and overly-simplistic “You should…”

The simple way that this phrase goes wrong is by under-estimating the resource complexity of a task:

Example: working with a client where I wanted to re-design a landing page on their site to improve it. Unfortunately I was under-estimating the number of people who need to be involved since the landing pages were still owned by the product team and are technically part of the same codebase as the full tech product. So a “small” change required detailed security scrutiny and QA before going live. Making “simple” changes was not in fact simple at all here.

But there’s also under-estimating the political complexity of the task:

Example: working with the NYTimes cooking team I suggested that they should re-tag their content. This kind of “you should…” recommendation seemed straightforward but neglected the political considerations - the team had just spent 6-figures on re-tagging all their recipes - so to ask for further budget to re-do a task they had just done would lose them face internally. A “straightforward” change that actually carried a bunch of political baggage.

Some other types of complexity that you might be under-estimating with regards resource allocation:

- Regulation/compliance complexity - which either prevents you even doing your recommendation or makes it slower.

- Technical complexity - while something might be technically easy, doing it with the client’s existing technology might be hard.

- Data complexity - a simple seeming request on the surface (make a landing page for every neighborhood) might actually depend on a robust, maintained data set that doesn’t yet exist.

- Maintenance complexity - even if the initial request to create something or do something is not resource intensive, it might come with an implicit agreement to continue to maintain it - expanding the resources allocated.

- Production complexity - where what you’re proposing isn’t that expensive or resource intensive to do, but the client (for whatever reason) has a higher quality threshold, making the recommendation more expensive/slower/harder than you anticipated.

- Narrative complexity - where what you’re recommending seems reasonable but either the company has tried it before, or a competitor has tried it before or there’s a general sense that “this doesn’t work”. Which can make your recommendation extremely hard to actually get done.

2. “You should…” is too prescriptive in form

In addition to under-estimating the problem, we also over-fit the solution. After all, as we saw in the chapter The Consultant’s Grain, as independent consultants we often bias towards our own natural strengths and areas of expertise.

When we say “You should…” we’re essentially offering a problem diagnosis AND a solution at the same time. The consequence of this is that we’re essentially asking the client to accept or reject both together.

Instead, most of your work would be more effective at actually changing clients if you stopped to clearly separate the diagnosis from the solution. If you don’t properly win over all the necessary stakeholders at the client’s side you’re going to face resistance trying to get anything done.

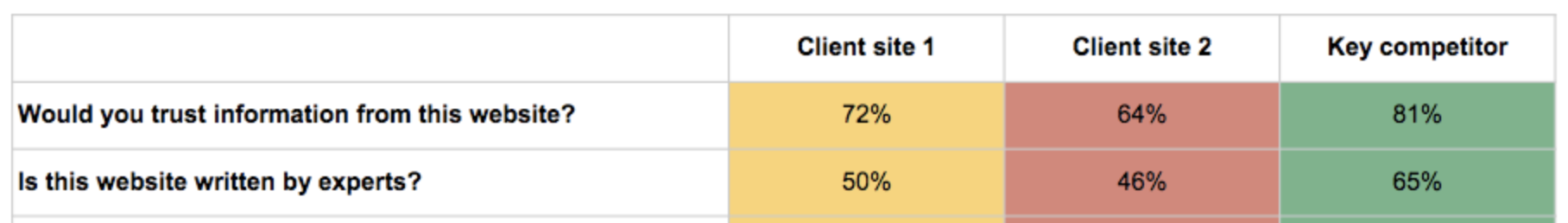

Example: I was working with Gartner Digital Markets on some SEO strategy and I felt that we needed to work on some more transformative work than simple technical SEO fixes - their core landing pages were offering a worse user experience than the competition and we were losing ground.

Persuading the rest of the organization that this was a problem wasn’t straightforward. We’d been saying that these pages needed overhauling and it felt like no one was listening. So we ran a small user survey to ask a series of 10 “Google quality rater questions”. This allowed us to present our findings to the senior leadership team at Gartner and I remember showing something like this:

Instantly, people leaned in around the table and there was a lot of executive interest. Saying something like “we should improve our pages” is too bland and generic - it only serves to win over people who already agree with you. It lacks any kind of rigor or weight to win someone over who already has their own opinions and roadmap.

In this situation - the survey allowed us to quantify the problem correctly and provided compelling evidence, we didn’t even need to offer a solution! Articulating the problem was enough to convince the necessary teams to take action and prioritize work.

So if you’re asking “You should…” to the client, stop and examine if you’ve properly defined the situation and provided evidence for the problem, to help the client deeply internalize the problem and win over the necessary stakeholders before you propose any kind of solution.

A good mental exercise to ensure you’re doing the work here is to ask yourself: what happens if the client takes no action? What is the consequence of the current trajectory, or the null case of no investment? This will help you bring some rigor to the question of what the consequence of the problem truly is and allow the problem to be quantified relative to other projects and investment opportunities.

So, what’s the alternative?

“There is an opportunity to…”

This phrase is the key - it places the focus correctly on first defining the problem - and then providing evidence - before focusing on the solution. It allows us to articulate and quantify the opportunity while leaving room for the client to have say over resource allocation, for the client to shape the solution and for the client to determine prioritization and timing.

Of course in reality, you’re often involved in shaping the solution too - but it’s crucial to ensure that you’re not skipping over the step of clearly defining the size and shape of the opportunity before getting to the solution.

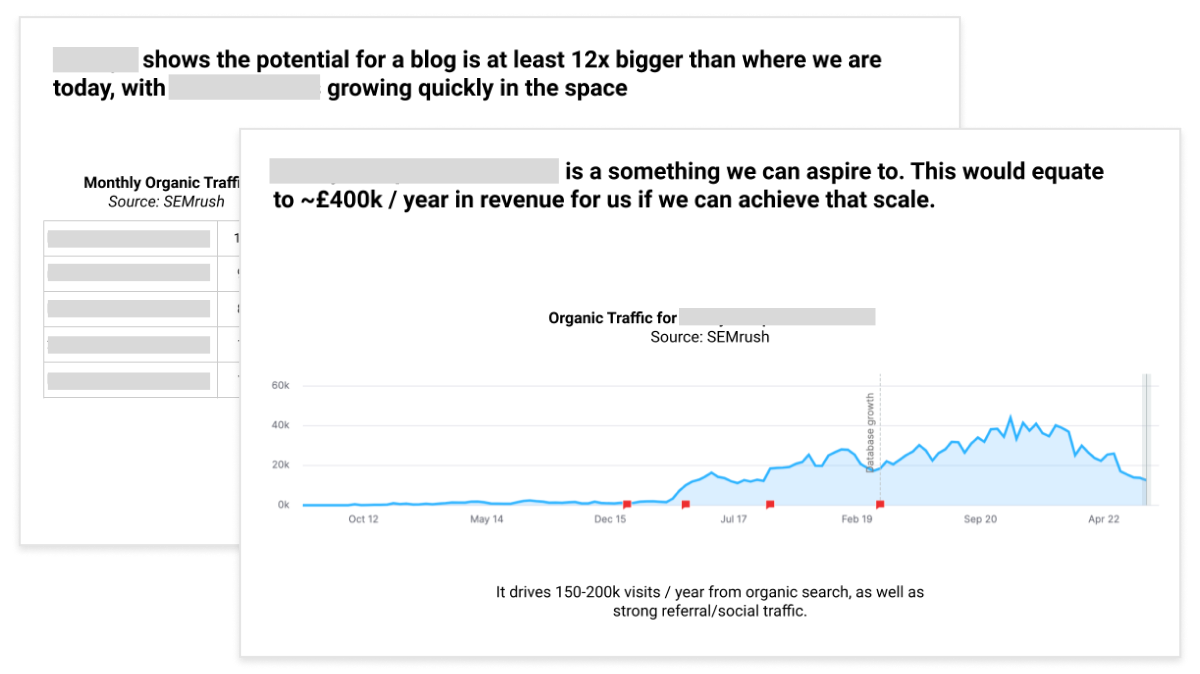

Example: Working with an ecommerce site to define an SEO strategy part of my recommendation involved investing in content strategy to drive links, traffic and conversions - but before even getting into the shape of the solution, i.e. how we would invest in content it’s important to articulate what the opportunity is.

By looking at relevant competitors we can estimate the potential traffic and revenue opportunity:

By showing what’s possible, clients are able to feel more invested in designing the solution with you, rather than just being told what to do.

This can also be uncomfortable! There are many situations where quantifying the exact opportunity is difficult, requires estimation or requires a different approach (like we saw with the Gartner surveys).

But consider the alternative - the alternative is recommending something to the client… because we say so?

This isn’t necessarily wrong - there’s value in expert opinion - but in my experience clients deeply appreciate you clearly separating out expert opinion and judgment from evidence-based analysis.

As David Maister says in the Trusted Advisor - the best approach is:

A good process for the advisor to follow is:

- Give them their options

- Give them an education about their options (including enough discussion for them to consider each option in depth)

- Give them a recommendation

- Let them choose

This stance essentially allows you as the consultant to own the diagnosis and quantification of the opportunity and then collaboratively with the client to shape the solution and prioritization.

Let’s look at the problem together

Taking a collaborative stance with your client is powerful. There are many aspects of consulting that are almost combative by nature - like pointing out problems the client has (that the client was complicit in creating!).

As we saw in the chapter Optimism as an Operating System, walking into a client with a critical eye can create a distance between you and the client.

Instead you want to create a kind of shoulder-to-shoulder stance with the client, facing towards the problems together. This creates a much safer, judgment free way to look at the problems (and opportunities) facing the client.

In fact, for senior executives - sometimes you really can’t give them advice - they’re too type-A and overly confident. The only way to convince them is to help them see the problem in a new light - to see things as you see them.

This idea is demonstrated beautifully by Timothy Gallway in The Inner Game of Tennis where he recounts teaching a senior executive how to improve their backhand:

One day in the summer of 1971 when I was teaching a group of men at John Gardiner’s Tennis Ranch in Carmel Valley, California, a businessman realized how much more power and control he got on his backhand when his racket was taken back below the level of the ball. He was so enthusiastic about his “new” stroke that he rushed to tell his friend Jack about it as if some kind of miracle had occurred. Jack, who considered his erratic backhand one of the major problems of his life, came rushing up to me during the lunch hour, exclaiming, “I’ve always had a terrible backhand. Maybe you can help me.”

I asked, “What’s so terrible about your backhand?”

“I take my racket back too high on my backswing.”

“How do you know?”

“Because at least five different pros have told me so. I just haven’t been able to correct it.”

For a brief moment I was aware of the absurdity of the situation. Here was a business executive who controlled large commercial enterprises of great complexity asking me for help as if he had no control over his own right arm. Why wouldn’t it be possible, I wondered, to give him the simple reply, “Sure, I can help you. L-o-w-e-r y-o-u-r r-a-c-k-e-t!”

But complaints such as Jack’s are common among people of all levels of intelligence and proficiency. Besides, it was clear that at least five other pros had told him to lower his racket without much effect. What was keeping him from doing it? I wondered.

I asked Jack to take a few swings on the patio where we were standing. His backswing started back very low, but then, sure enough, just before swinging forward it lifted to the level of his shoulder and swung down into the imagined ball. The five pros were right. I asked him to swing several more times without making any comment. “Isn’t that better?” he asked. “I tried to keep it low.” But each time just before swinging forward, his racket lifted; it was obvious that had he been hitting an actual ball, the underspin imparted by the downward swing would have caused it to sail out. “Your backhand is all right,” I said reassuringly. “It’s just going through some changes. Why don’t you take a closer look at it.” We walked over to a large windowpane and there I asked him to swing again while watching his reflection. He did so, again taking his characteristic hitch at the back of his swing, but this time he was astounded. “Hey, I really do take my racket back high! It goes up above my shoulder!” There was no judgment in his voice; he was just reporting with amazement what his eyes had seen.

What surprised me was Jack’s surprise. Hadn’t he said that five pros had told him his racket was too high? I was certain that if I had told him the same thing after his first swing, he would have replied, “Yes, I know.” But what was now clear was that he didn’t really know, since no one is ever surprised at seeing something they already know. Despite all those lessons, he had never directly experienced his racket going back high. His mind had been so absorbed in the process of judgment and trying to change this “bad” stroke that he had never perceived the stroke itself.

Looking in the glass which mirrored his stroke as it was, Jack was able to keep his racket low quite effortlessly as he swung again. “That feels entirely different than any backhand I’ve ever swung,” he declared. By now he was swinging up and through the ball over and over again. Interestingly, he wasn’t congratulating himself for doing it right; he was simply absorbed in how different it felt.

After lunch I threw Jack a few balls and he was able to remember how the stroke felt and to repeat the action. This time he just felt where his racket was going, letting his sense of feel replace the visual image offered by the mirror. It was a new experience for him. Soon he was consistently hitting topspin backhands into the court with an effortlessness that made it appear this was his natural swing. In ten minutes he was feeling “in the groove,” and he paused to express his gratitude. “I can’t tell you how much I appreciate what you’ve done for me. I’ve learned more in ten minutes from you than in twenty hours of lessons I’ve taken on my backhand.” I could feel something inside me begin to puff up as it absorbed these “good” words. At the same time, I didn’t know quite how to handle this lavish compliment, and found myself hemming and hawing, trying to come up with an appropriately modest reply. Then, for a moment, my mind turned off and I realized that I hadn’t given Jack a single instruction on his backhand! “But what did I teach you?” I asked. He was quiet for a full half-minute, trying to remember what I had told him. Finally he said, “I can’t remember your telling me anything! You were just there watching, and you got me watching myself closer than I ever had before. Instead of seeing what was wrong with my backhand, I just started observing, and improvement seemed to happen on its own. I’m not sure why, but I certainly learned a lot in a short period of time.” He had learned, but had he been “taught”?

This is about tennis (is it?) but equally applies to consulting! I find in my own work that senior executives are often blocked by some inability to see what’s actually going on - and that telling them is useless! Instead you need to help them see it for themselves.

Because of their distance from the day to day work, senior executives are especially prone to replacing some version of reality with a compressed narrative. And when this compressed narrative is wrong in some key way you need to return to first principles to show them (not tell them!).

Much like we saw with the example of the Gartner surveys - helping clients see with fresh eyes what’s really going is powerful and can be profoundly useful before you even begin suggesting solutions.

Understanding the problem in all of its emotional and political complexity

Once you adopt this collaborative stance with the client you begin to see that the problems as you thought you understood them, are not in fact the full picture.

Your sense of “what’s going on” with a client is intermediated by your point of contact and it turns out that your client is an unreliable narrator. Remember - best case they have problems they’ve been unable to solve on their own, worst case they were actively responsible for creating the problems in the first place!

So it’s no wonder that clients often down-play, mis-represent and mask the full emotional and political complexity of what’s going on. Especially when you first start working together and haven’t yet earned their trust.

But for you to do your job it’s crucial that you get a full picture of what’s really going on. And further, clients deeply appreciate a consultant that can listen and observe closely enough to see what’s really going on.

As David Maister says in The Consultant’s Role:

“It can be unsettling to find that the client is primarily interested in having his or her problem understood, in all its emotional and political complexity, as a precondition to having the problem diagnosed and solved.”

What this is saying is that you need to earn the client’s trust in order to be effective at your job. This isn’t at all obvious! When a client comes to you asking for a “content strategy” or support “hiring a VP marketing” it all seems so straightforward, rational and well defined. But as you unpack the layers of the onion you begin to realize why it’s been so hard for the client to help themselves. And that’s when the emotional and political complexity of the problem starts to come into view.

Developing a sensitivity to the emotional and political context of client problems requires an active listening and sensing instinct on behalf of the consultant - to use your own lived experience inside the client’s organization as a way to sense what the inner work life is like inside your client’s business. As Ruth Orenstein says in her book Multidimensional Executive Coaching:

For the time he/she is present, the consultant becomes part of the multidimensional system, both influencing it and being influenced by it. To do the work of executive coach- ing, then, the consultant must be able to tolerate, and ultimately make use of, entering a highly complex place-a place that is occupied by neither the individual nor the organization alone but, because of their convergence, both the individual and the organization together; a place that contains both the exigencies of working life and the impulses of the psyche; and a place that engages and, in turn, is engaged by the consultant’s own intrapsychic material. In addition, if the work is done effectively, it requires that the consultant be both involved enough in the dynamics so as to experience their impact and detached enough so as to analyze what is transpiring. These demands make imperative the use of oneself as tool.

Remember: when clients first come to you, your first instinct might be to dismiss the problem as “easily solved”. But you need to hold space to truly consider that the thing that seems easy is, in this particular situation, with this particular client actually not at all easy. And that’s when the work begins.

The Next Most Useful Thing

This all builds up to my personal consulting mantra: always work on the next most useful thing.

This mantra helps remind me that consulting isn’t about being right, it’s about being useful.

As a consultant - it’s crucial that you’re generating momentum, that clients can feel a sense of progress in your work. A consultant is typically an expensive investment and without a sense of progress or momentum your engagement will stall out.

Importantly however, a sense of progress and momentum doesn’t have to come from the official SOW or project plan. Actual progress is one thing - but a sense of progress is just that - it’s about your client feeling like things are moving forward.

In fact, depending on the project and the client - moving at the expected pace can be too slow! Even after agreeing on a scope, project plan and set of next steps, moving as fast as you said you would can be disappointing to the client.

Remember - building a great client relationship is about trust. And doing the minimum doesn’t build trust. So it’s important to demonstrate to the client that you’re willing to do the extra work, to go a little further, to do the unexpected.

This doesn’t require a ton of extra time but it does require some deliberate effort and sensitivity - to think about the client’s reality - the meetings, projects, pressures they’re facing right now - and think about how you can proactively support them.

You could re-draw the diagram from up above as follows:

Whether your client is facing an important decision, or preparing for a board meeting or working through a bunch of menial tasks - whatever it is there’s typically a way for you to help out in some small way. And in doing so the client feels a sense of momentum and builds a sense of trust between you.

What’s the next most useful thing?

It’s not about ignoring the SOW or the project plan but it’s about recognizing that there’s value in giving your client a sense of momentum.

Example: I worked with a B2B saas client a few years ago - they were a small startup looking to raise their series B round and we engaged to create a content strategy.

On this project I made a mistake and despite the fact the client didn’t have any in-house editorial resources I took their request at face value and we structured the project around a 6-week content strategy.

I delivered what I think is good quality work with a deeply researched and evidence-based 66-page strategy for producing content and…. Nothing happened? They were happy enough with the work product but it didn’t lead to any material change in their strategy or an ongoing consulting relationship.

In hindsight the key mistake here was not asking myself enough what the next most useful thing was. I think if I’d been more honest about what would add value and show momentum for the client it would have been either a) condensed one or two slide summary of the content opportunity for their fundraising deck and/or b) supporting their VP marketing recruitment effort.

Perhaps I should have done both. Either way - it turns out that what the client wanted wasn’t really what the client needed and this mismatch led to a fairly unproductive engagement.

Recognizing that clients are unreliable narrators when it comes to scoping projects and defining timelines allows for a more philosophical view of value when it comes to consulting.

Is a 6 week strategy project really the most useful thing the client needs right now? What happens at that point when we have the strategy defined - then what? By seeking more context, clarity and insight into momentum we can more easily work on things that the client will truly appreciate, not just provide things the client asked for.

A Conclusion About Owls

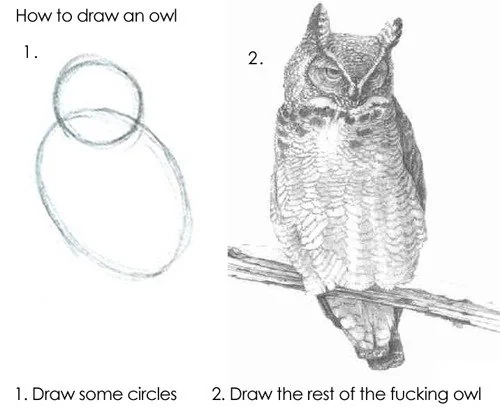

There’s an internet meme about giving advice that I love. It’s an image that shows you how to draw an owl:

Too much bad consulting work looks like either step 1 or step 2. Either you’re telling the client “draw some circles” and the client is frustrated the advice is too basic and high level. Or you’re telling the client to “draw the rest of the fucking owl” and are ignoring the detailed reality of the situation and the limitations of teams, resources and capabilities.

Or worse, the client asked you for help drawing owls but what they’re really doing is painting a woodland scene…

Think about this image next time a client comes to you for help drawing owls - your first response shouldn’t be “Oh, that’s easy, first you draw some circles”, it should be “Show me how your owls look today. What do you think is holding you back from drawing better owls? And why is drawing owls important to you right now?”

Remember - it’s about adopting a collaborative, trusted stance with clients. And that might require resisting your initial urge to give advice. Instead you need to listen to the full emotional and political situation and then work with the client to re-examine reality in new and surprising ways.

Always work on the next most useful thing. And that doesn’t always involve doing what the client asked for.

Previous

Previous