The roadmap is not the territory

Notes on sequencing, strategy maps and business knowledge

Most of my consulting work connects to “marketing strategy” in some way - clients come wanting to talk about growing their business. But the funny thing about growth and marketing is that each component is like a thread that, once pulled, unravels the whole spool.

- Struggling with distribution? How’s your analytics?

- Struggling with SEO? How’s your product?

- Struggling with content? How’s your narrative?

- Struggling with margin? How’s your sales?

Every question seems to open up an interconnected mess.

It’s why I start every consulting engagement asking 1,000 questions. I’m trying to understand the context of the client environment, trying to see how all the threads are interconnected.

So it’s been fun recently to do a few projects that look like a “full business review” where I work with a team on strategy, but explicitly putting the whole business on the table as context. I’m thinking about scaling up and formalizing this offering so I’ve been musing about where the value is for these sessions, what clients want, and where clients get stuck.

The format for these business review sessions today is:

- Initial exploratory kickoff to align on objectives

- Prep work to get up to speed with the quirks of the business and review existing data and documents

- Two-day workshop (in a remote world typically spread over 3-4 sessions)

- A summary presentation that captures the key ideas from the workshop

Given my background, these sessions typically focus on growth, but the nice thing about expanding the frame from a typical consulting engagement is we deliberately put everything on the table: operations, process, people, funding etc. It’s useful to try and look at the business as a whole so that when we get into the weeds with a particular problem (which we inevitably do) we can keep the broader business context in mind.

It’s surprising how useful this broader company context is - I get the impression that most leadership teams really don’t give themselves permission to zoom in and out from macro to micro in the same session - and this causes a lot of bad decision making.

The tension of course with these workshop sessions is that “strategy” and “roadmaps” are abstract concepts and not particularly useful. What can you accomplish in a two-day session that has real value for a client?

In early conversations with clients we usually settle on “prioritization” as the tangible output, as in - we’ll come out of the two days with “a prioritized roadmap” or a “set of strategic priorities”.

The reality is a bit messier than that - the value from the session typically ends up a mixture of: clarity around the big picture, combined with a few very specific key breakthroughs which unlock immediate action on projects.

This could be a useful insight around content distribution, or an insight about SEO success, or an insight around job responsibility for an upcoming hire, or a key way to separate or integrate different business units.

In the end, prioritization isn’t really the useful thing.

The roadmap is not the territory

Prioritization sounds concrete but isn’t actually that interesting. Clients already know roughly what to do - and have a prioritized roadmap already. So what’s the problem?

The challenge facing the client is typically some underlying feeling that what is currently on the roadmap today won’t prepare them correctly for tomorrow’s future. There’s a belief that they need to do things differently or do new things to prepare for the changing future.

The real challenge typically ends up being “how do we invest in doing NEW things, given our existing prioritized roadmap?”. The client is looking at an existing roadmap, trying to add brand new things to it and so imagines that a new version of the prioritized roadmap is what they need.

But the challenge runs deeper. Doing things differently, or doing brand new things is HARD for organizations. You have to fight against existing roadmaps, existing biases, existing goals, existing routines and processes.

And, crucially, it’s not about a well defined roadmap where we understand the variables. It’s impossible to forecast and roadmap a future for activities we don’t understand yet. How much will it cost to invest in this new channel? How fast can we see success doing this new thing? How many pieces of content can we create using the new process?

Management is prediction, and it’s hard to predict new things

Businesses are learning engines and management is prediction. Cedric Chin is writing a wonderful series right now on management as prediction and what that actually means in practice:

What does it mean to be data driven in business? Most people think being data driven means looking at charts on a daily basis. Or they attempt to use data in their orgs, and then fall into one of the many traps that come with the territory. How do you actually get good at using data for your operations? And how do you build the mindset and the organisational capabilities necessary to do it?

The key here is that for a business that wants to do new things - you need to, well DO THINGS before you really understand how they work or what the effects are. They’re new after all!

So here we start to realize that maybe a prioritized roadmap isn’t the real goal - what we need is something that can guide us, but has plenty of room for learning, refinement and experimentation along the way.

Sequencing is like prioritization with more unknowns

While not explicitly asked for, during these workshops I often end up creating a kind of sequencing view of their roadmap. If you think of strategy as the most abstract, and a roadmap as the most detailed - then a sequence is somewhere in the middle.

I really like this diagram from Casey Winters’ post on the realities of a CPO role:

Casey goes on to talk about not making a new strategy, but enforcing better sequencing of their existing strategy. We know what to do, but enforcing some sequencing can bring a sense of clarity to what we’re doing NOW and what we’re doing NEXT. Something weirdly missing from a lot of strategy (which often comes down to 5 things we should be doing right now).

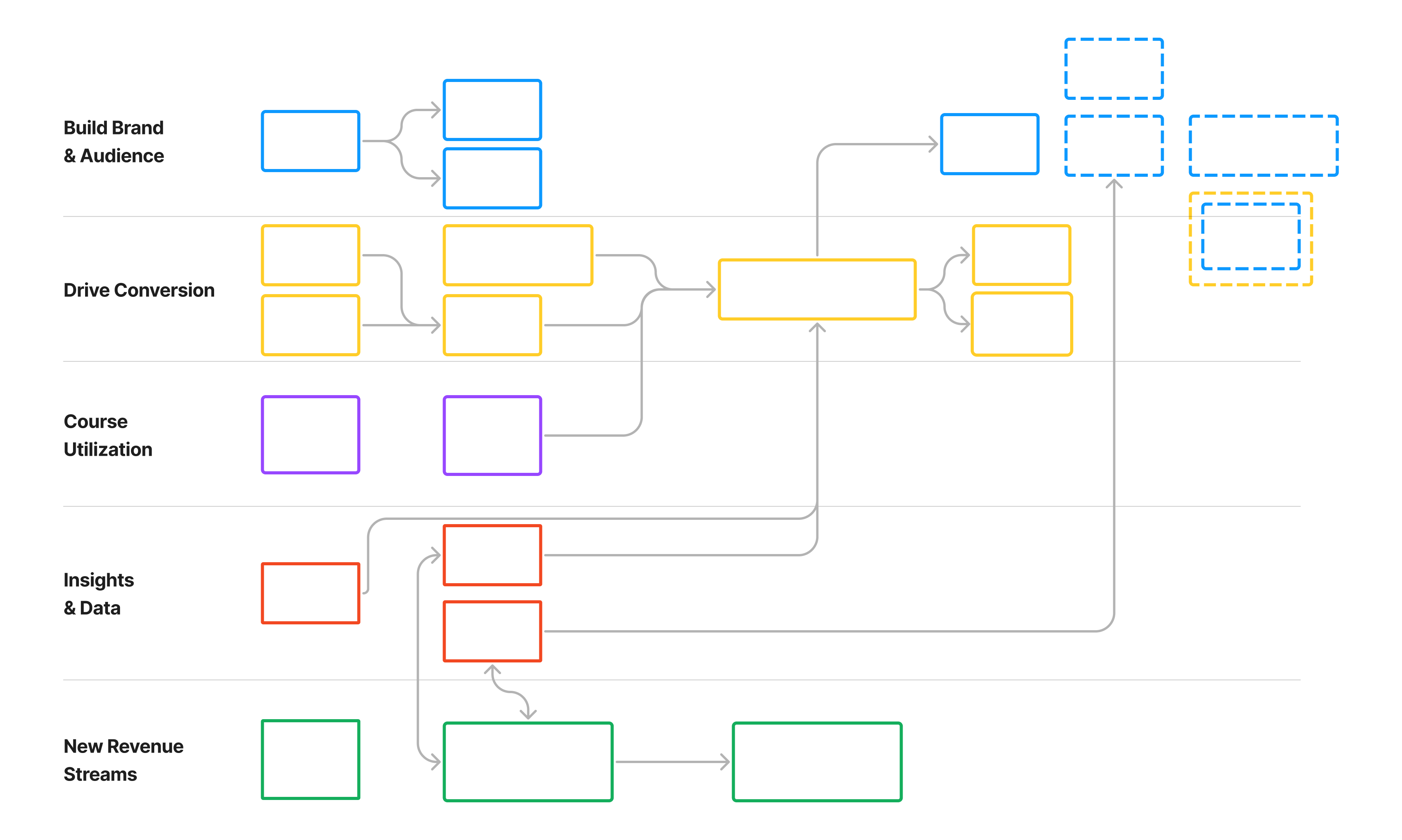

Here’s an example of a sequencing that came out of a consulting engagement with a business that sells online courses (with key details removed obviously):

There’s a lot here - mostly because what this diagram shows us is what NOT to do. It allows us to choose a lane and focus.

This isn’t really a prioritization (it doesn’t tell us what to do first) and isn’t really a roadmap (it doesn’t tell us when things will happen) but it still adds some clarity by ensuring the various opportunities in front of us are connected and dependent in various ways.

Maybe the real value for a sequencing map like this is to help us understand how to get started with new things, and what we can expect to learn along the way. It’s making the unit of progress learning, not time.

Tradeoffs and Revealed Values

Of course you’re still left with some choice - which things do we pursue first? How do we choose between the various paths we could follow? Once you really start to explore this idea you realize that there’s far more individual belief and values work going on than you might assume for “the world of business”.

I love how Vaughn Tan breaks this down in the description of his Boris workshops:

Your tradeoff pattern shows more about your values than the goals you’re trying to achieve. A clothing company demonstrates different values if it is willing to use cheaper high-pesticide, water-intensive cotton than if it insists on only using low-input cotton in its products. What you choose to do and not do reveals what is and isn’t important. This is another way of saying that what a person or organization implicitly believes is valuable (or good, or moral, or worthwhile) determines the tradeoffs that are made.

Different people and organizations have different tradeoff patterns because they have different values, different resources, or different constraints. Usually, all three forms of difference are at work.

Revealed values are really important - especially in small teams.

It’s why I’ve started referring to product/market/founder fit instead of product/market fit. Again, the problem with most clients is not that they don’t know what to do - they know what to do, but they don’t really understand why they’re not doing it. This leads to personal frustration and burnout. So it’s key to try and design a strategy that isn’t an abstract ideal but actually aligns with the capabilities, values and beliefs of the team that is going to have to execute them…!

In a two-day workshop, how much can you change beliefs and values? You can’t. But you CAN help with alignment between team members.

Gaining clarity on the principles

Just like values, where there is surface level alignment but once you dig it unravels, there is also principles. Independent of the specific initiatives and measured goals, what are we trying to do?

Most clients cheerfully say something like: we’re trying to grow!

But when you start to unpack that, trouble starts - growth at all costs? No, of course not. Growth via raising capital? Oh lord no.

It turns out there often isn’t a well articulated higher level objective. Nathan articulates that well in his piece on problems with prioritization:

9. Define an organizing principle

When anything goes, it’s impossible to choose between competing alternatives. There must be some strategic frame against which to measure ideas. But too often, the framing of this goal is taken for granted. Startups obsess over weekly growth rates, and public companies obsess over margins—but these are goals, not strategies. The best companies choose narrative frames in addition to measurable goals that help them stay focused.

For example, at Substack we cared about week-over-week growth like everyone else, but we also had organizing principles like “attract quality writers who are ready to go full-time on paid newsletters” that helped us organize our roadmap. For Lex, our current organizing principle is to build the best “first draft” writing experience in the world. If we only thought about the metrics we would be lost.

When I was more junior in my career I never really understood the idea behind creating a list of principles for a project or team. It all seemed too abstract and management-speak. Of course it IS management-speak. Principles are essentially a compression of a strategy so that they can survive contact with different teams and different team members.

As Nathan mentions here - a narrative frame for a project can be a powerful guiding force as you navigate the unknown roadmap of doing new things.

In conclusion: Giving Clients New Ways of thinking

Ok, so this post is far too long and rambling but here’s the reveal - maybe (maybe!) the real value for these workshops is helping clients find new ways of looking at their business reality.

If we accept the premise that strategy is a fluid, evolving thing - what is the most useful outcome from a moment-in-time intervention? For it to have enduring value I think it must allow us to think through situations we have not yet encountered. New tools for thinking through problems and situations.

Ways for an executive team to upgrade their thinking. Of course, no one is going to buy that directly, but I think it’s the real job to be done for this kind of workshop.

So, with that frame in mind the outcome for this kind of “total business review” workshop is some combination of these four dimensions:

1) New dashboards embed new ways of seeing the world. A dashboard1 is essentially an embedded mental model for how the business works - and if you can help the client create a new dashboard you can help them see the world in new ways. This is often a precursor to doing new things and doing things in new ways - because they suddenly have a measurement framework for it. You manage what you measure after all.

2) Sequencing is about what NOT to do, and what we need to learn. Roadmaps imbue a false sense of confidence in the future but the reality is that if we want to do new things, or do things in new ways we need to DO things so that we can learn. Learning how they work, learning whether we’re able to pull them off, learning how resources intensive they are. So a sequencing is a middle ground between abstract strategy and detailed roadmap.

3) New narrative frames. Operating within the context of the individuals, beliefs, cultures and biases of the team you’re working with it’s about seeking new principles, new clarity and new naming for ideas that seem important but hard to gain consensus on.

4) Capabilities & process insights. There’s often a few key insights that come out of the two day session that help unlock next steps on key projects. Putting this through the lens of learning - these tend to function a bit like accelerated knowledge - you get to skip a few loops of do -> learn -> do by working with someone who knows the space, or has done it before.

Maybe, after all that the real value add is clarity.

“ambiguity is the psychological malaise in which both mediocrity and evil thrive – an imperceptible sludge surrounding any endeavor defined by quality and vision

— Maxim Leyzerovich (@round) July 20, 2021

the most potent antidote to the toxicity of those unable, or unwilling, to offer leadership will always be: clarity”

If you’re interested in one of these workshops - get in touch.

-

See my post here on executive dashboards and why I find them so interesting. ↩

August 22, 2025

June 27, 2025

Google is Grounded and Needs to Learn How to Soar

March 21, 2025

This post was written by Tom Critchlow - blogger and independent consultant. Subscribe to join my occassional newsletter: