Navigating Power & Status

How to get things done inside organizations by understanding power potholes and status switching

This is part 4 of the Yes! And… series. Start with part 1 here.

In chapter 3 we looked at the difference between “problem solving” and “capacity building” consultants. Reframing consulting as capacity building opens up the ability to work on long open-ended projects with a fundamentally collaborative stance with the client. Per Paresha & Philip1:

“Long-term fulfillment of social obligations, as part of a community of practice.”

Unlike problem solving - capacity building fundamentally requires the consultant to learn how to get things done within the “community of practice” of the client’s organization - working across a wide range of teams, people and projects.

The consultant - operating on a faster feedback loop than an employee - needs to learn how to map the org, sense the flow of power, and set the correct status all within a short span of time in order to get things done.

Mapping & navigating an organization requires appreciating that the org chart is a political map, drawn by those at the top of the organization and holding certain symbolic and functional power. But also only crudely (if at all) mapping to the actual power flows and status games inside an organization.

Getting things done and changing an organization begins with understanding the power dynamic of the people and teams involved.

Let’s start with the org chart and gradually peel away the layers to get to deeper concepts like power potholes and status games…

Part 1: Mapping The Org Chart

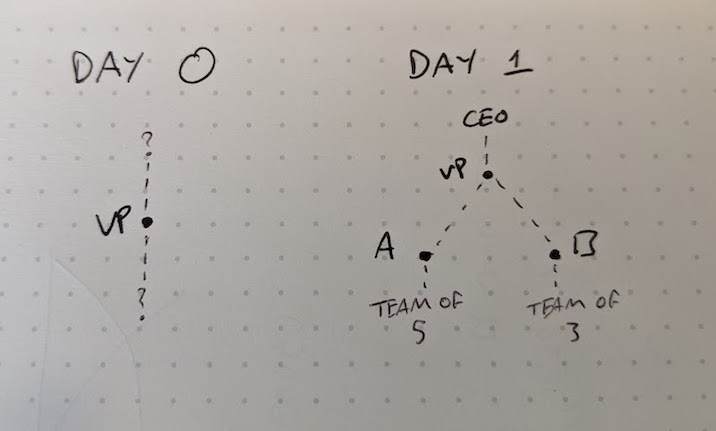

At the beginning of an engagement the org chart is all we have. Mapping an org chart starts simple and scrappy and rapidly evolves to something more useful. Here’s a sample sketch to illustrate how it works (and yes I often literally sketch these in my notebook):

Day 0 - initial contact - typically I don’t get much more information than the position title of the person looking to hire - “VP Marketing” or something similar.

Day 1 - the first day of work - you meet a few people and begin to develop a rudimentary working assumption of the local org chart around your point of contact. So maybe there’s two teams that report into the VP and you have a name for the person running each team but little more.

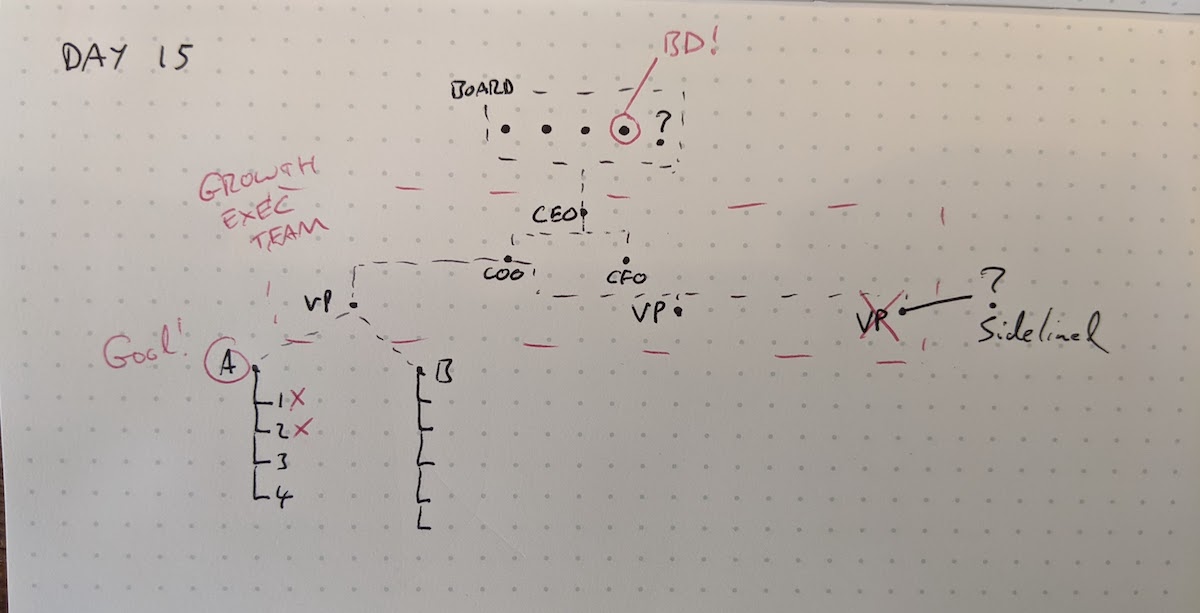

However, especially in cases of embedded work where I’m on-site with the client, by day 15 my understanding of the org chart might look something like this:

At this point our fictional org chart map starts to show some new features:

- The VP point of contact is now situated relative to the CEO, relative to the growth executive team

- The CEO is loosely situated relative to the board

- Certain actors on the map are “cancelled” - closed door conversations suggest certain VPs are on their way out (or have lost the faith of the CEO)

- Conversely, it’s becoming obvious that some actors are more effective than others - able to get things done inside the organization

While this model of the org chart continues to evolve, it becomes less useful as a tool to “navigate” the organization. The legible connections between teams and people are clearer but the underlying power structures are only just starting to emerge.

An Org Chart is designed for legibility not accuracy

Sketching out the org chart is helpful in the early days - but org charts are incredibly simplistic when it comes to actually mapping the organization. As Venkatesh says about org charts:

“A good deal of the process is about imposing anxiety-alleviating platonic structural beauty.”

The org chart of boxes and lines shows reporting structures in a legible way, but does little else. If you’re using the org chart to get the “lay of the land” it’s necessary to understand its limitations.

The org chart tells us about the topology of the organization, i.e. the formal connections between people. It tells us nothing of the topography, i.e. the lay of the land. The messy distortions.

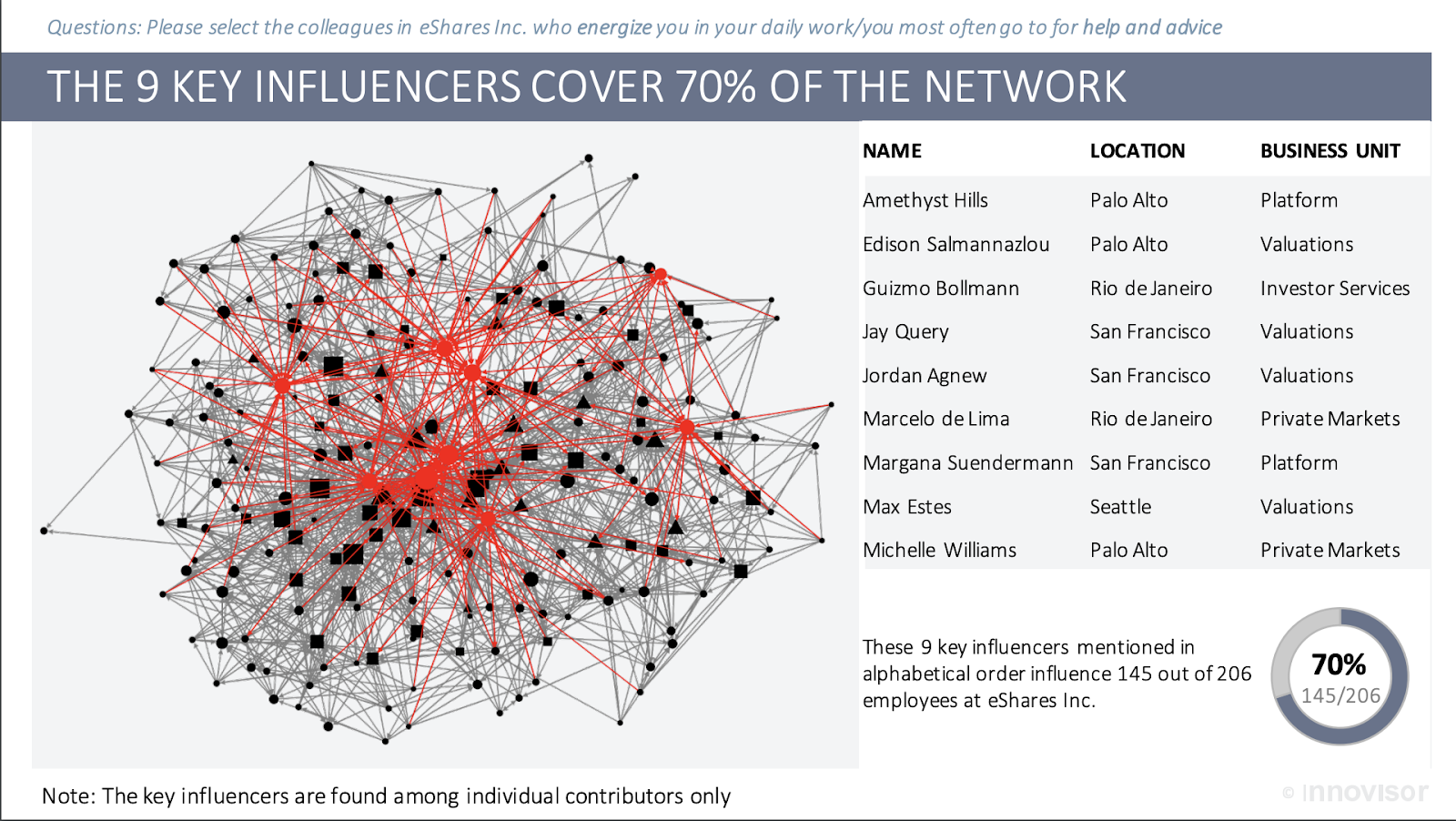

Layering influence on top of a network topology starts to give a clearer picture of what’s really going on:

This illustration comes from a fascinating analysis that Carta conducted examining the influence inside their organization.

This network-model showing a small number of highly connected nodes accurately represents the lived experience of working inside a dynamic and complex organization.

These network graphs however only tell you so much about power. The node graph above shows influence & communication channels but not necessarily power flows.

For the consultant attempting to get things done - relational power dynamics are everything and as much as you’re understanding culture inside an organization, you need to understand the flows of power.

I start on day zero with a crude org chart sketched in my notebook, and over the first week convert the org chart into a network graph which then grows into a crazy wall2 with key power players mapped.

Understanding Localized Power

Once you’ve mapped a few organizations - you begin to realize some key insights. Firstly - power is often centralized in a very small number of people. And these people are not always found in the c-suite.

There are three common types of people who hold power inside organizations - decision makers, gatekeepers and makers:

Decision makers are the most common and most obvious type of power player - typically these are executives or senior employees. The kind of people who need to be consulted to make a decision - or have the latitude to make decisions themselves. One type of decision maker you might forget to pay attention to is the in-house expert with a history of success:

Example: I worked with a client where the executive team was mostly the usual suspects (i.e. old white dudes) but anytime the executive team got together they included a more junior senior director. This senior director had managed to get inside the inner circle not by seniority but by expertise - he was an expert at SEO strategy and when making decisions that impacted SEO the senior executive team would defer to him. This in-house expert can hold significant power because for certain decisions the exec team defers to them for sign-off.

Gatekeepers come in two common forms, gatekeepers of time and gatekeepers of data. Executive assistants control significant power through owning executives time and schedule. Less obvious are those people who control access to data:

Example: I had a client where a small in-house data team was responsible for pulling reporting, generating analyses etc. The organization lacked robust dashboards or shared views of data so almost all requests for data went through the data team - this led to the situation of the senior leaders in the org consistently putting requests through the data team. This caused the team to wield significant power (while also overwhelming themselves via constantly getting urgent requests from the exec team).

Makers are the least commonly understood power nodes in my experience. On the one hand it’s as simple as - those who can make things hold power - but on the other hand that doesn’t quite capture the unreasonable power that (often relatively junior) employees can have through being able to make things. This is especially true for people who can combine skillsets in unique ways:

Example: I worked with a publishing client a few years ago and I worked with a series of editors. Each responsible for a section of the website. Only one editor however combined the ability to make content with the sufficient know-how in HTML & design to actually build new and innovative content experiences (i.e. page templates, in-line elements etc). As a result this editor ended up being a significant source of power - often pulled aside by senior execs to help build something new, prototype a new idea or just make something better in a hurry.

There’s one universal rule to spot power nodes - look for who gets brought into the room.

When an executive stops the meeting to demand someone else should be in the room - that’s a sign of significant power. When a conversation constantly references someone’s name (e.g. an exec assistant) that’s a sign of significant power3.

The Behavior of Power Nodes

Once you realize that power is localized into a small number of people and that they are spread across the org chart - you need to pay close attention to the way those people operate. Their ways of working - while they might seem trivial - represent an opportunity for the consultant to accelerate their own learning curve and learn to get things done inside a client’s organization.

One example of this localized ways of working is what Venkatesh calls “calendar weather”:

Consulting Tip #11: Pay attention to calendar management practices in client organizations, especially around senior executive schedules, and chat with admins whenever possible to learn the typical patterns of calendar craziness and how they cope.

— The Art of Gig (@artofgig) June 5, 2019

“Calendar weather” is a great example of a small way of working - a localized piece of organizational culture that can have outsized impact when viewed through the lens of network graphs.

A key individual in the system can have mental models, ways of working or personal habits that can become associated with “the way to get ahead” or “how to get things done”. Emulating these ways of working and adopting them for your own projects inside the organization can instantly give you momentum.

Power Potholes

The opposite of localized power is power potholes. Areas of the org chart that at first glance might look safe (“they’re a VP! They should have buy-in and the ability to get things done!”) but when leaned on turn out to be weak and can’t support your weight.

In the early days of a client engagement - watch and listen closely for unusual instances of cause and effect - i.e. when someone says or does something that doesn’t make sense. When something that you think should usually or rationally lead to X instead leads to Y you’re usually missing a hidden undercurrent of power.

Notice turns of phrase, rejected ideas or a statement that turns the room to silence. These mis-steps are power potholes in the consultant’s path. Notice them, write them down, meditate on them, and try and ask yourself: what power structures exist here to explain this anomaly?

Example 1: in my own consulting work I led a design sprint to build a new product within the organization, using a VP as exec sponsor. Unfortunately, only during the project did I realize that the VP was weak and lacked buy-in and support from the other execs. In theory that VP should have supported that project but in practice, like stepping in a pothole accidentally, the system jolts and the project stalls for non visible reasons.

Example 2: In the early stages of a client project I’m trying to coordinate a new workstream - and I suggest that the editorial director can lead the review of existing content. I haven’t met this person yet and I’m leaning on the org chart and job titles. This idea gets rejected and new options emerge. This gives me pause in the moment (why not the editorial director?) but only later in the project do I realize that the editorial director is out of favor with the executive team.

Power potholes and localized power nodes matter for full-time employees too. Employees, however, have the luxury of time to settle into and understand power structures.

The consultant on the other hand, is on a tighter timeline and often operating cross-functionally far more than traditional employees so understanding these dynamics, and understanding them quickly is critically important to effective strategy work.

To wrap part 1 of this piece - it’s clear that to get things done inside a client’s organization you need to create your own map. Something more nuanced than the org chart that maps the flow of influence and power. Once you have this map you can better understand how things get done.

This perspective mostly treats the consultant as a silent observer. Now, in part 2 let’s more closely examine the role the consultant plays as an outsider entering and disrupting these power flows.

Part 2: The Consultant Has No Place on the Map

Understanding the flows of power on the map is one thing - understanding your own place in those flows is another entirely.

As we map the org chart and the network graph we begin to see: the consultant has no place on the map.

Capacity building consulting requires necessarily working across functions, teams and people. Momentum for new capacity inside organizations comes from getting buy-in and wind in your sails - which requires some kind of strolling across the organization4.

However, as you stroll across the organization there’s often no fixed home for the consultant, no stable identity to tie back to. The best you have is your executive sponsor as an anchor to the org chart, but even that can be tenuous depending how much autonomy you have.

I like to imagine the consultant as a quantum structure on top of a classical map (the org chart). While the map is fixed and tangible, the quantum structure behaves strangely and has bizarre properties like non-locality. This non-locality of the consultant brings with it an uncertainty with regards to power structures.

Employees inside the organization settle into a stable view of the existing power flows, while the consultant creates an unknown quantity - partly as an outsider and partly because capacity building explicitly requires building or re-arranging parts of the existing power structures.

For employees, status relationships are often stable and clear inside organizations. Not only who you report to but a vague sense of “who am I senior to” and “who is senior to me”.

But the consultant has no place on the org chart - in fact they “move around the org chart” constantly.

Example: an 18 month engagement might see me working across design, product, editorial, strategy, content, marketing etc over the course of the engagement as various projects and needs arise. This can be a mix of senior projects working with the VP Product or a small fast project working directly with the freelance content writers. The high/low and lateral movement across the org chart can be far and wide.

This lateral movement across the map requires a minimum social capital and charm to be able to appear in meetings or across teams without offending stakeholders. Winning hearts and minds across the org. This is a very high stakes and nuanced game5.

The only way to play this high-stakes game is by realizing and recognizing status games.

Status Games & Transactions

Because the consultant has no place on the map - they have no assigned status. This is unnerving at first and brings with it a unique challenge - the consultant has to set their own status.

It can be a shock to realize that your status relationships are not fixed - you have to set your status relationship with each person you meet individually.

This means that you might end up with strange non-continuous status relationships - i.e. you might be above the status of the VP of marketing in one context, but below the status of a marketing manager in another:

While this might seem esoteric - status has ultimate power in determining your social interactions. Here’s a quote from the book Impro by Keith Johnstone:

‘Try to get your status just a little above or below your partner’s,’ I said, and I insisted that the gap should be minimal. The actors seemed to know exactly what I meant and the work was transformed. The scenes became ‘authentic’, and actors seemed marvelously observant. Suddenly we understood that every inflection and movement implies a status, and that no action is due to chance, or really ‘motiveless’. It was hysterically funny, but at the same time very alarming.

There is a lot to unpack once you start noticing status transactions, particularly once you start to think of status as something that can be changed (again, from Impro):

All our secret maneuverings were exposed. If someone asked a question we didn’t bother to answer it, we concentrated on why it had been asked. No one could make an ‘innocuous’ remark without everyone instantly grasping what lay behind it. Normally we are ‘forbidden’ to see status transactions except when there’s a conflict. In reality status transactions continue all the time. In the park we’ll notice the ducks squabbling, but not how carefully they keep their distances when they are not.

As you establish status with everyone you meet your aim should be a “minimal” status gap, as Keith suggests. Aiming to be slightly above or slightly below their status provides the most fruitful and effective environment to get work done.

But when to set high status and when to set low status?

Strategy, Stewardship & Status

I’ve written before about my mental model for retained strategy projects: strategy & stewardship6.

What’s interesting about these two modes of work is that they often require blending different high/low status ideas.

Effective work looks something like this status 2x2:

Working with executives: strategy is default high status, stewardship is default low status.

Working with employees: strategy is default low status, stewardship is default high status.

Let’s unpack that:

Strategy Status

During periods of strategy work there are typically two modes of working:

- Gathering insights, data and knowledge from across the org

- Presenting work to execs or sparring with execs

In 1) the consultant has to stroll across the organization and attempt to get knowledge, buy-in and insights from employees who likely have little clue who the consultant is, and have not worked with them before. Personally - I find the mode of low status most helpful here. Attempting not to assert authority but rather persuade that helping me gather information is useful for them too.

Conversely - in 2) I find the correct posture is high status. Executives almost universally thrive on confidence and presenting a strategy roadmap usually requires equal parts real experience and some projected confidence and enthusiasm for the ideas.

Stewardship Status

When working on stewardship projects there are typically two modes of working:

- Running processes, project management & operations

- Reporting & communicating those projects back to the exec team

Here - the status is flipped. For 1) the most useful status is high status - essentially acting like a manager and leader to ensure that the wheels are turning, projects are shipping on time etc. Providing leadership and clarity for teams you’re working with that “things are OK” and “here’s why we’re doing this”.

And in 2) we’re acting more like a VP than a consultant - presenting low-status to report “up” to the exec team on what’s going on.

Remember that “high status” is more correctly “just above the status of the executive” and “low status” is more correctly “just below the status of the executive.

Why does this all work?

Working with Executives - long term retainers work best when you start high status, i.e. where you can be the expert in the room. But over time no executive wants to stay low status so you have to switch at some point to them telling you what to do. This is a direct result of shifting from strategy to stewardship.

Working with Employees - every employee is threatened by external consultants coming in so you have to begin by playing low status - this way you can gain their confidence. Then as you increasingly gain context for the business and knowledge of how they work you can switch to high status to begin owning stewardship initiatives you outlined early.

Fast Status Switching & Improv Strategy

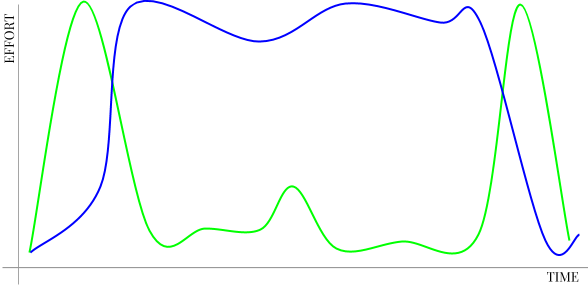

There’s one more wrinkle. If we recall this chart of strategy (green) and stewardship (blue):

We see that neither line ever truly hits zero - there’s always some combination of strategy and stewardship.

And we know that strategy relies on spontaneous moments (see: the serendipity deficit from chapter 1).

A defining characteristic of executives is the ability to hold a short-term and long-term view at the same time. So a single interaction might blend both short-term priorities, tasks, operations and long-term vision and mission questions.

So as a consultant operating in the theatre of work, it’s possible that you have to switch status between tasks in a single day, or even harder - switch status within a single conversation!

Let’s take a look at this sample conversation to illustrate (highly simplified and exaggerated):

Exec: Hey, when are we presenting the roadmap to the board?

Consultant: The meeting is set for next Thursday, but that means Mark the VP of product can’t make it because they’re on vacation.

Exec: Ok, do we have everything we need from Mark before he heads out on vacation?

Consultant: Yes. But actually I think we should remove the product section of the roadmap. I think we’re already presenting a complicated roadmap and we don’t have enough confidence in the product parts of the roadmap. I think it would undermine our confidence that we have elsewhere in the org. Let’s take that section and trim it down to a few slides to show the full roadmap and impact as coming later.

Can you spot the status switch? Let’s mark up the same conversation:

Exec: Hey, when are we presenting the roadmap to the board?

Consultant [low status]: The meeting is set for next Thursday, but that means Mark the VP of product can’t make it because they’re on vacation.

Exec: Ok, do we have everything we need from Mark before he heads out on vacation?

Consultant [high status]: Yes. But actually I think we should remove the product section of the roadmap. I think we’re already presenting a complicated roadmap and we don’t have enough confidence in the product parts of the roadmap. I think they would undermine our confidence that we have elsewhere in the org. Let’s take that section and trim to a few slides to show the full roadmap and impact as coming later.

Status-switching mid-conversation is a learned skill and much like a good consultant has to master context switching they must also master status switching.

Conclusion

Navigating a client’s organization requires appreciating that the org chart is a political map, drawn by those at the top of the organization and holding certain symbolic and functional power. But also only crudely (if at all) mapping to the actual power flows and status games inside an organization.

The consultant - operating on a faster feedback loop than an employee - needs to learn how to map the org, sense the flow of power, and set the correct status all within a short span of time in order to get things done.

Thanks to Toby Shorin, Brian Dell, Sarah Hunt, Ollie Glass, Alex Moseman, Katy Cook, Paul Millerd, Alexa Scordato & Doug Van Spronsen for reviewing early drafts of this piece.

-

From this foundational article in The Systems Thinker: Consultants as problem solvers or capacity builders? ↩

-

Take a scroll through crazywalls.tumblr.com and imagine every image a consulting gig! ↩

-

Sharp eyed consultants will notice that the natural insight here is that these three types of power roles are roles that consultants can play to gather power and influence. Getting brought into the room as a consultant is crucial so look for ways to become a decision maker, gatekeeper or maker. ↩

-

An informal knowledge of what’s going on in different neighborhoods inside the org. Sometimes literally strolling. ↩

-

Some examples of how this is high-stakes. You can get stuck when you show up - becoming a cog fitting into an overstretched team. Or get pigeonholed as having a single skill to offer. These are difficult traps to avoid and spot coming. Thanks to Alex Moseman for highlighting these issues. ↩

-

If you’re catching up read this section: strategy & stewardship: a framework for retained clients ↩