Ways of Seeing

How to recognize and understand culture inside a client's organization

“One thing about which fish know exactly nothing is water, since they have no anti-environment which would enable them to perceive the element they live in.” - Marshall McLuhan

“First, The fish needs to say, ‘Something ain’t right about this Camel ride – And I’m Feeling so damn Thirsty.’” - Hafiz

As a consultant it’s important to recognize that one of the strongest forces inside an organization is their culture. It’s why my personal mantra is a reframing of the classic:

(Their) culture eats (your) strategy for breakfast.

It’s my theory that to be an effective consultant you need to learn how to understand culture - you need to learn ways of seeing your client’s organization. In this post I’ll walk through some frameworks and concepts for doing just that.

But I’ll go one step further and suggest that understanding an organization’s culture is the whole game and that teaching your clients to see is the ultimate pinnacle of a consultant’s work.

First though, a walk in London some time ago….

A walk with an anthropologist in London

A few years ago I was walking with a friend through the streets of London. I’d been working at Google for a while and I was frustrated at not being able to get my ideas turned into reality. My friend, a philosopher and anthropologist, just laughed at me and said: (I’m paraphrasing - sorry H)

“You’re an idiot. There are thirty thousand people working at Google. If everyone as far down the food chain as you could get their ideas made it would be chaos. The system is explicitly designed to prevent your individual ideas from mattering one bit”

This was a lightbulb moment for me. Of course. Every organization is a system and process designed for certain outcomes - while some change is accepted and embraced, the point of the organization - its structure, processes and hierarchy - are there to prevent individuals from derailing the whole machine.

The rhetoric of “ideas can come from anywhere” and “act like a startup” sound good but they’re just not true reflections of the lived experience inside a large organization like Google (or any other). The truth is that large organizations are both explicitly and implicitly designed to prevent too many new ideas from emerging.

The Frustration of Stability

As a consultant or changemaker, this frustration can be very common. You are convinced that you have a good idea but feel unable to convince the organization. Or you have convinced the organization on an idea but feel frustrated that you just can’t get it done.

It’s important to recognize that most organizational change happens very slowly and starts very small. And this is as it should be. Consider the alternative - can you imagine an organization that was reinventing itself every time a consultant walked in the door?

This frustration is an emotion you can channel into focus. Changing a stable organization requires first understanding its context. And when you walk into a client’s office, you’re always missing context. Sometimes there’s business context you’re missing - funding, acquisitions, business models. Sure. But more often it’s about missing cultural context. Your ideas are being rejected like a virus by the antibodies of the company.

Ever since writing The Consultant’s Grain it’s become a mantra of mine that “(their) culture eats (your) strategy for breakfast”. It’s a reframing of the classic “culture eats strategy for breakfast” and it helps me stay focused - especially as a consultant coming into an unfamiliar environment and trying to get things done1.

However, the client usually isn’t paying you to understand their culture so you have to do it fast. I think this is a skill, something you can learn. This skill of sensemaking takes experience of different cultures and a strong sense of observation.

Enter John Berger

Art has a lot to teach the business world. It’s the best place to learn the skills of sensemaking and observation. John Berger had a wonderful TV show on the BBC in the 70s called “ways of seeing”. The opening scene is a thing of beauty.

Without talking, John walks to a renaissance painting, framed on the wall of a gallery and pulls out a knife. The gentle ripping of the canvas is all you hear as he carefully cuts out a portion of the painting. It’s a shocking scene that instantly makes you pay attention.

The whole thing happens in the first twenty seconds. Watch it here:

It’s an unsettling scene - even when you know it’s coming! Recognizing why this scene is shocking helps us understand culture. No one tells you if the works on the wall are priceless. But the signals are all there - a gallery setting. A TV show about art. You’re not expecting him to walk up with a knife… It’s not what’s done.

John Berger goes on to talk about critical ways of understanding art, primarily through learning to critically examine something in front of you by keeping the context in frame. Who is showing this art to you? What sensory cues are there to shape your perception? How does reproduction of the image affect the image itself?

These questions and ways of seeing are the same exercises I employ as soon as I engage with a new client. Attempting to actually see what’s there - not what everyone around you assumes is there, and certainly not what you’re told about “how things work”.

I just came off a project where after a large acquisition there were two teams learning to work together. This caused incredible frustration for both sides - both everyday frustrations at different processes and approaches but slower moving structures below the surface about values and mental models of how the world works. These caused tensions, clashes and more.

I won’t pretend to have solved all of these frustrations (and I wasn’t being paid to solve these - at least not directly!) but the very first thing you can do in this situation is try and look critically and honestly at what is there.

Especially when you’re early in a project, before you’re supposed to have gained any knowledge it’s a great time to try and provoke some reactions (whether you go so far as slashing a painting is is up to you!). By pushing against the system in new and interesting ways you can learn a lot about the system by how it responds.

You need to get in the client’s flow

To understand context and get a feel for culture, you need to find ways of getting “close enough to smell the client”.

Context and culture happen at the in-between moments, spaces and projects. How does the team handle crisis? How does the team handle group meetings? What does down-time look like? How are new team members welcomed onto the team?

If you’re too distant from these in-between moments it’s almost impossible to properly understand the culture.

So as a consultant - as an outsider - it’s crucial to find ways to get embedded inside the organization. You need to get close enough to be inside the flows and streams of work. Increasingly there is a duality - the physical environment and the digital one - where different modes and types of work get to happen.

It’s important to be present in both.

Being physically present gives you a sense of the emotional interactions, in-between spaces and so on. It also gives you the platform necessary to build the emotional capital required to ask for favors.

Being digitally present gives you the tactical understanding of how projects, documents and tasks flow around. It’s also a great way to get a glimpse of the knowledge work happening around you that you aren’t directly involved in.

Once you’re inside the flows it’s your job to pay attention.

Understanding Culture 101 - what are we trying to see?

It’s helpful to have some frameworks to help us think through the kinds of things we’re trying to see in the first place.

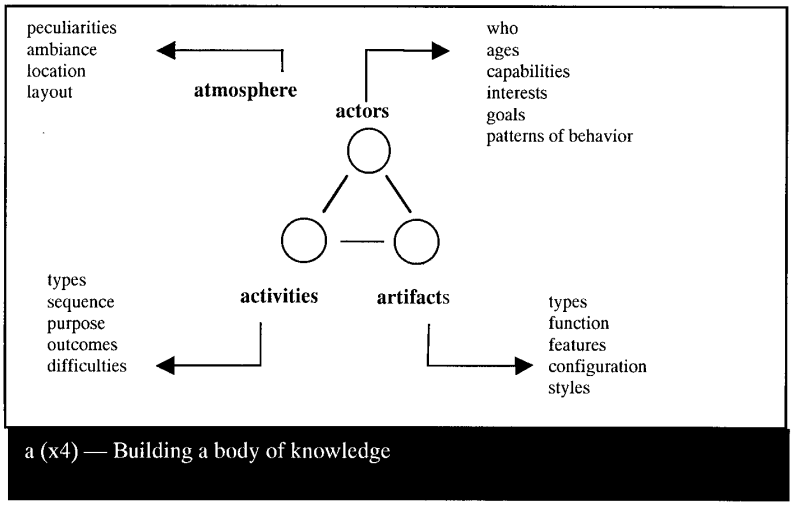

This framework from ethnography2 is a simple and memorable framework that shows how you can think about the ways culture can manifest and reinforce itself (the four A’s):

In this framework the actors, artifacts and activities interact directly with each other. And they all exist within a wider atmosphere.

Actors - these are the people in the frame. I love the word “actors” since everyone is performing a role. The theatre of work is the epic play of our lives and the office (both physical and digital) is the stage. Notice how people behave, the language they use and their intrinsic motivations.

Artifacts - these are the visible extensions, the “tangible” assets created by the actors. This might be everything from the design of a report to the structure of a paid leave policy.

Activities - the things that the actors do and why they do it. These activities will tell you more about the underlying power structures. In particular, pay attention to the habits and routines that are in place. Nothing will tell you more about what people value than what they do repeatedly.

Atmosphere - this is the wider environment in which we’re working. Is the team or organization part of a bigger structure? How is the physical office laid out? In the digital space are they using Slack or Basecamp and what is the tone of conversation there? Which design choices were put in place deliberately and who made them?

There are many frameworks and mental models that can help you understand and grapple with culture. ”Principles of Management”, chapter 8 is a great primer on organizational culture and has a model for the 8 “dimensions” of organization culture3.

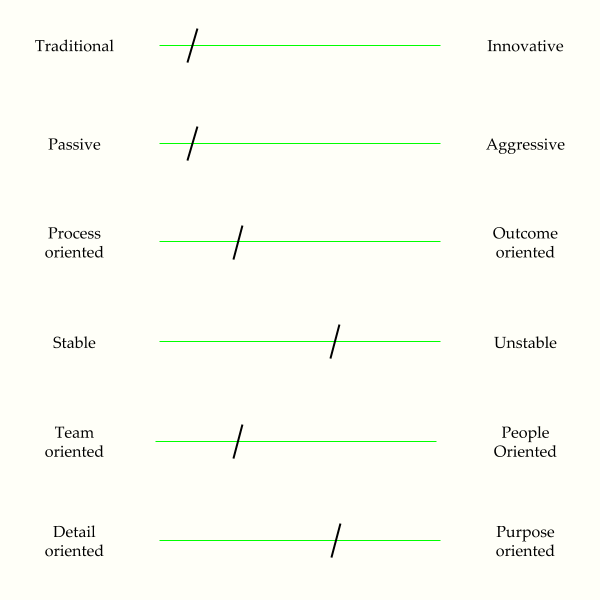

You can imagine every organization as having each of these aspects to a greater or lesser extent. So you might think about “plotting” a company along each axis. This is an example I put together from a recent client engagement:

You can see for example that I’ve mapped them as “unstable” and “process oriented” - which makes sense since my role with this client engagement was to create new processes.

I’ve found this framework helpful when trying to distinguish between things like intrinsic motivation (e.g. “we want to build the best X”) vs extrinsic motivation (e.g. “we want to beat competitor Y”).

Once you start plotting an organization on these dimensions of culture you can start to look at each one and think about why they are that way and how they reinforce that behavior.

How to see the world through your client’s eyes

When you’re trying to understand a company’s culture, you’re essentially trying to understand how they see. The lens through which they process the world around them.

This manifests in three specific things to pay attention to: language, delusions & mythology.

Language

The naming of things is incredibly powerful. First a group will create language as shortcuts for ideas and values - ways of thinking. But gradually this language starts to create the group. First the group creates the language and then the language creates the group. Language is the reinforcing feedback loop of culture.

There are two extensions from this - firstly that using the wrong language can alienate you from a group. As a consultant I try hard to use a variety of definitions, terminology and linguistic approaches. Using the wrong term once is no big deal, but consistently referring to the concept that the group has learned to reject will get you rejected as well.

Secondly - a skilled poet or linguist can create new language for groups. Language that has embedded values, ideas or bias from the consultant.

My friend Brian calls this skill noticing and naming. It’s the essential task of the consultant to pay close attention and then attach new language to important ideas4. By naming things you can drive attention to what’s important and hence shape the way an organization behaves.

For a wonderful poetic read on the power of language in organizations I’d encourage you to read Notes on the Role of Leadership and Language in Regenerating Organizations, a.k.a. The Little Grey Book.

Look at this quote from The Little Grey Book by Dr. Michael Geoghegan

Managers understand the organization’s past behavior.

But this knowledge,

and the language that accompanies it,

limit their vision

of the organization’s potential future state.

Using the language of the past,

managers may try to provide a vision for the future.

But it is an old future

a memory of what the future could be.

Managers may strive for fundamental change,

but their language prevents them from achieving it.

The whole book is worth reading and has tons of wisdom, especially on the pragmatic nature of introducing new language and the efficiency of old language5.

Shared Delusions

Shared Delusions - In order for teams to function effectively they need a shared mental model of how the world works for their industry/niche.

This mental model helps the team act quickly by working from a shared cheat-sheet of understanding. It saves having to make every decision from first principles. I like to call this mental model a “shared delusion”.

Why a shared delusion? Because it’s useful to recognize that any mental model of how the world works is an incomplete model. The idea of a shared delusion is that we’re understanding head first that we’re lying to ourselves about certain things to make it easier for us to make decisions or rationalize our behavior.

The problem is that many mental models (i.e. shared delusions) about the world are built implicitly and not explicitly so that it becomes hard to tell which piece of the mental model is a useful simplification and which piece of the mental model is an oversimplification (or a flawed assumption).

So let’s call the mental model what it is - a delusion - and try and understand how we look at the mental model directly to better understand it’s limitations and flaws.

As a consultant - with experience likely across more industries than those inside the organization - you are in a unique position to separate out which parts of the shared mental model of the world are useful shortcuts and which are flawed ideas. Reinforce and strengthen the useful shortcuts (or make new ones) while deconstructing and weakening the flawed ideas.

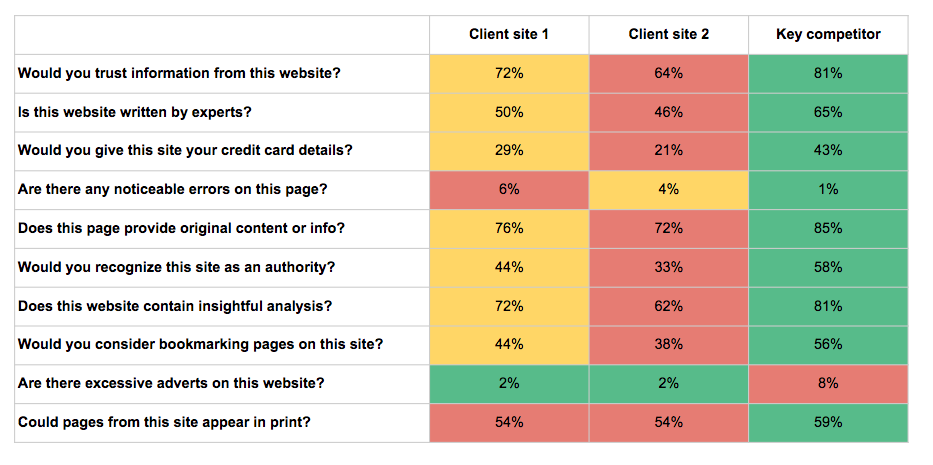

I’ll give you an example from my own work - a B2B client had seriously under-invested in design. Partly under the assumption that in the B2B space “it wasn’t as important as for B2C” and that their sites were “good enough already”. These kinds of assumptions about the world were repeated and interpreted differently throughout the organization but no one was challenging them directly. I wrote more about the methodology over in my post how do you measure good content but a survey against their competitors was akin to taking a knife to their painting. It sent a shock through the organization and I presented this table at an executive all-hands:

There’s two lessons here - firstly if you want to understand shared assumptions sometimes you have to go to the source - surveying users, asking customers questions, etc.

Secondly - always try and create an objective counter to their subjective reality & be gentle when challenging mental models - no one enjoys their view of reality being broken.

Mythology

Mythology - In times of stress, culture is a strong force that binds teams together. Culture can be the light at the end of the tunnel. Connections and bonds are formed in times of struggle and stress. From these challenging times come stories - stories of how it went down. Stories of heroics, stories of failures, stories of late nights, stories of product launches.

These stories become mythology within the organization. Very rarely are these documented - we’re looking for the oral history of the company and you’ll often get the best version of these out of the office. (At the bar or on the walk to lunch).

Pay attention and listen carefully to the mythology - actively look to uncover these stories of projects past. These stories, often-repeated, contain lessons about value systems within the organization. But the lessons they tell usually bear little to no resemblance of truth of what might succeed or fail in the future.

The key insight here is that every single new project will get compared to the myths. So you can’t understand the context of your ideas and recommendations without first understanding the mythology.

Tread lightly when following the footsteps of glory or failure - both are dangerous paths to follow.

Culture vs Propaganda

Beware documented culture. For all of this talk about company culture I’ve found that it can be misleading to rely on mission decks and documented company values. These are top-down objects that are at best out of date and usually contain at least one statement that is the opposite of the truth6. A mandate rather than an observation. (After all the only reason to document culture is to change it.)

My favorite illustration of corporate propaganda is Facebook’s “culture” of “move fast with stable infrastructure”. It’s a mock up of a poster that Zuckerberg is showing at a conference where the letters are on screen taller than he is, literally larger than life:

The interesting thing is that the only images you can find are the keynote mockups of the poster. There appear to be no actual posters of this manifesto.

I’d go further and say that it is an impossible object. It’s impossible to make a poster with this phrase on. Why? Because anyone (and especially Facebook employees) who reads this poster is actually translating it in their mind into the actual poster of “move fast and break things”. Nothing has changed about their culture.

So seek out the internal culture decks, they’re useful starting points. Consume them. But don’t trust them.

Three Breakthroughs

The first breakthrough I had as a consultant was to understand that there is very little objective truth in business. What works for one business doesn’t always work for another. Every strategy is a reflection of the business you’re working with and the environment they’re in. There is no “just do X” recommendation in the real world, only in dusty, discarded strategy documents. This quote has stuck with me from Tomasz Tunguz’s Overfitting in Business:

As I study and meet and analyze more and more businesses, I find myself drawn to the idea that each is a snowflake. Each startup is unique composition of its team, in the circumstances of its genesis, and the ecosystem in which it blossoms. Business concepts like the ones mentioned above can provide a common language about ideas. They can help us tell stories to motivate and inspire. Perhaps, they can provide some form of analytical framework.

But until the success of these theories can stand the test of reproducibility or time, that’s all they should be. After all, even some of the most successful CEOs in the world cannot reproduce their success the second time or third time. Building a business is really hard, and building an enduring company even more so, because each enduring business is built in a different way.

The second breakthrough I had was to understand that there is a depth to observing a business. Learning ways of seeing, recognizing culture as a powerful force and attempting to observe the realities of the organization rather than passively taking for granted the received wisdom leads to strong insights.

Without ways of seeing the premise of consulting falls apart - you make generic recommendations that are easily rejected by the organizations belief systems and culture. Recommendations that fail to create new language or any meaningful change.

The third breakthrough I had - from reflecting on past client engagements, sometimes lasting years - was that the most important and most meaningful work I’ve done for clients is to help them see. Help them see their own culture in new ways, or help them see the world around them.

By sharing these ways of seeing with your client you can develop a shared perspective of the road ahead.

Teaching your client to see

“A people or a class which is cut off from its own past is far less free to choose and to act as a people or a class than one that has been able to situate itself in history.” - John Berger

And so, finally we arrive back where we started. How do you teach ways of seeing? How do you challenge assumptions, create new contexts or add new naming?

Watching Ways of Seeing the first time was useful to help me see. The second time was useful to help me teach others how to see.

Re-watch the first twenty seconds. We can hear the gentle ripping of the canvas in a new perspective. Why is this scene so unsettling? Why is it effective?

So take a good look at the client and when you are seeing clearly, take a knife to the walls and help them see what’s there.

–

Much love to the folks who contributed and reviewed drafts of this piece including: Kit, Brian, Toby, Sean, Robin, Susie, Rachel, Thomas, Elan & Erin

If you made it this far (firstly thanks!) but you might be interested to know this was a bit of an experiment. I’m consciously trying to extend my writing to be a little longer as I gear up to write a book on consulting for independents. For now, I’ve collected all my strategy writing here.

–

-

In The Consultant’s Grain I explore more deliberately the difference between working on projects that go with the grain or against the grain of an organization via the idea of consulting fast and slow. I’m not going to repeat all that here but if you enjoy this piece queue that one up next! ↩

-

The full paper is worth checking out: Laurel Anderson and Paul Rothstein (2004) ,’Creativity and Innovation: Consumer Research and Scenario Building’ although in this context doesn’t give much else of use to understand organizational culture. ↩

-

I’ve slightly adapted the dimensions of culture presented in the book below to create axis but the original chapter is still very much worth reading, and it’s short. ↩

-

My friend Thomas makes a good point here that you need to be careful not to go overboard - attempting to add large amounts of language to a team will create confusion and also dilute the language being introduced. ↩

-

My friend Kit was wise to point out this might be framed slighty negatively - there is a ton of value of documenting culture and creating culture decks. It’s just my experience that you can’t completely trust them. But definitely don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater here. ↩

Previous

Previous